By Jeroen Zandberg

The FUEN Congress

(The article is also in Dutch and can be read following this link)

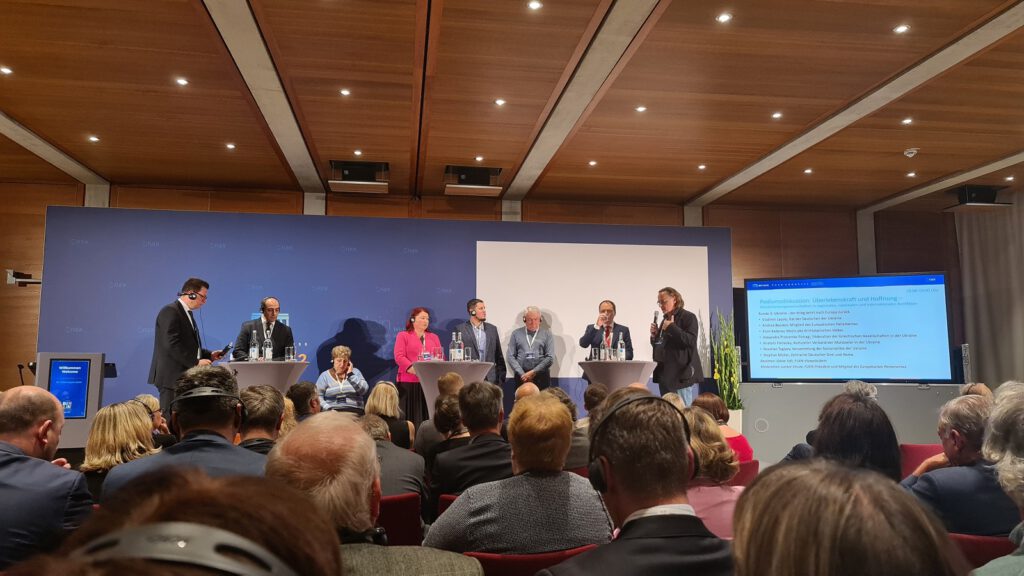

From September 29 to October 1, 2022, more than a hundred representatives of European minority groups gathered in Berlin for the annual FUEN Congress. FUEN stands for Federal Union of European Nationalities; an organization that unites more than a hundred European minorities. Founded in 1949, it is one of the leading advocates for minority rights in Europe with offices in Berlin, Brussels and Flensburg (northern Germany). The organization is largely financed by several German federal states and the German and Hungarian governments. In addition, there is a modest membership fee that must be paid by the members.

This time the annual congress paid a lot of attention to the war in Ukraine and its consequences for the many minorities in the country. Furthermore, many panel discussions took place on different themes, such as discrimination and language preservation, in relation to minority rights. The FUEN Congress was attended by many representatives of minorities and a large number of parliamentarians from different countries and the European Parliament. An extensive report of the congress can be found on their website.

Minorities are by definition in a marginalized social position since the culture of their community is not dominant and therefore offers limited access to the structures that make up society. Members of minorities are therefore by definition outsiders. During the three-day FUEN congress, there was therefore much discussion about the national structures that limit the members’ development. Much attention was paid to the various activities to break through this barrier of disadvantage, to prevent assimilation and to avoid conflict. The Minority SafePack Initiative (MSPI) presented to the European Commission by FUEN and others in 2018, for example, received a lot of attention again. The MSPI proposes a series of legislative changes to better protect national minorities so that they are able to preserve their language and culture. Although the initiative was embraced by the European Parliament, it was subsequently rejected by the European Commission in 2021. This decision is currently being challenged in court and might give the MSPI another chance to make European law more inclusive for national minorities.

Frisian representation

The Frisians were well represented at the congress. On several occasions the Frisian representatives shared the stage with other speakers to highlight the situation of the Frisian minorities. For example, the representative of the Council for the Frisian Movement (Ried fan de Fryske Beweging) was the keynote speaker at the ‘non-kin-state working group’. The representative of the Frisian council (Frasche Rädj) in Germany was also one of the four panellists during the discussion about language and identity. One of the vice presidents of FUEN, Mr. Bahne Bahnsen, is also a (North) Frisian and used his years of experience to steer various panel and organizational discussions in the right direction.

FUEN is organized in several working groups where minorities with similar situations discuss their activities and plans. For example, there is a working group for German national minorities and a working group for minorities with a national state, such as the Hungarian and German minorities in the Central and Eastern European countries. There is a working group for the Turkish minorities and one for the Slavic minorities. There is also a working group for minorities without a national state, the ‘non-kin-state working group ‘.

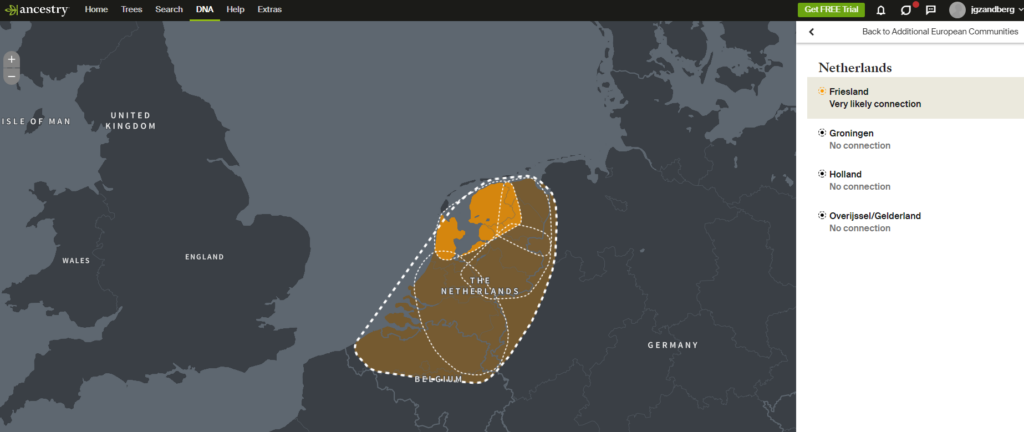

The situation in Friesland (Fryslan)

At the meeting of this working group, the Frisian representative of the Council of the Frisian Movement, Pier Bergsma, held an extensive speech about Friesland. In his speech he indicated that almost all inhabitants of Friesland (Fryslan) can understand the Frisian language to some extent, three quarters can speak it, but less than a quarter can also write it. He explained that the local and regional authorities actively promote Frisian. For example, the place name signs are mostly bilingual. He further emphasized the importance of Frisian-language media, such as Omrop Fryslan, in the awareness and dissemination of Frisian. He did note however that although there are volunteer initiatives for online news in the Frisian language, all Frisian dailies are published in Dutch. Mr. Bergsma also showed a video clip of a demonstration for the increased use of Frisian in education. However, the protesters had all passed their 60s, which raises the question of how much the cause is supported by those it is supposed to serve, namely children and their parents. He concluded his speech with the comment that it is not the government that ultimately determines whether the Frisian language survives, but that it is the people who have to keep a language alive.

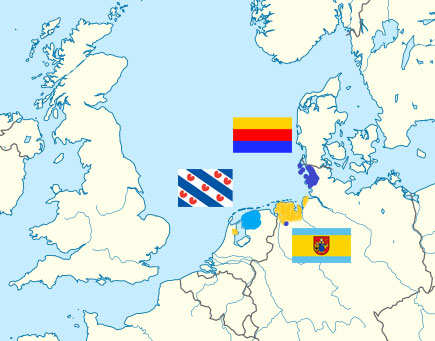

The four autochthonous national minorities in Germany

The Frisians are officially recognized in Germany as one of the four autochthonous national minorities. The other national minorities are the Danes, the Sorbs and the Sinti and Roma. The latter live scattered throughout Germany, while the other three, the Danes, Frisians and Sorbs, inhabit a clearly defined area. This recognition gives the four communities special protection and government support. An autochthonous national minority is an ethnic, cultural and linguistic community that has lived for many generations in a territory where it is now a minority.

The Frisians in Germany

The province of Fryslan has more than 600 thousand inhabitants, of which a large part is still somewhat fluent in the Frisian language. The situation in North and East Friesland along the North Sea coast in Germany deviates significantly from this.

The Frisian minority in Germany is linguistically divided into East Frisian (or Sater Frisian) and North Frisian. Spoken in Groningen and East Frisia (in Germany) until the late Middle Ages, Sater Frisian is now virtually extinct with less than a thousand active speakers in the municipality of Saterland. However, North Frisian still has fifty thousand speakers and is therefore comparable in number to the Danish (50 thousand) and Sorbian (60 thousand) minorities.

Digitization of the Frisian language

During the panel discussion on Friday, September 30 on language and identity, the representative of the Sorbian minority, Mr. Dawid Statnik of the organization Dawina, provided a hopeful look at the activities that the community is undertaking to strengthen their language and culture. He spoke enthusiastically about the collaboration with Microsoft. This collaboration has led to the accessibility of the Sorbian language in Microsoft products. Sorbian is now part of their translation module. I asked the representative of the Frisian council (Frasche Rädj), Ms. Ilse Johanna Christiansen, whether the Frisian minority in Germany also has such projects underway. For example, Frisian as spoken in Fryslan has been an integral part of Google’s translation module for several years now. However, this required a herculean effort for many years on the part of many Frisian organizations that had to supply sufficient Frisian texts to Google in order to train the translation algorithms. However, Frisian from North and East Friesland is far removed from Frisian as spoken in Fryslan. Mrs. Christiansen agreed that there are plans to make the other varieties of Frisian digitally accessible as well. After all, if a language is to survive in modern times, it is necessary that it goes along with the digitization process of society. However, it is questionable whether these plans to prepare Frisian for the future will go beyond the drawing board. After all, the Frisian languages in Germany are spoken by a small minority and the institutional support is minimal and mostly symbolic.

Government support for East and North Frisian

The Frisians are recognized by the German government as an autochthonous, national minority. This recognition gives them access to government support, whereby the Frisian minority received 1.3 million euros from the German government in 2021 to strengthen their cultural identity. The government support ensures, among other things, that the Frisian language has a place in education. About a thousand people are currently taking voluntary language lessons at schools in the North Frisian region. In addition, some primary schools pay attention to Frisian and once a week there is a three-minute program called ‘Frasch for enarken’ on the German public broadcaster NDR.

The other national minorities have similar goals, but different capabilities. For example, the Sorbs received 24 million euros and the Danish minority even received 104 million euros (from the German and Danish governments) to strengthen their cultural community. The Danish minority finances 46 secondary schools and 57 primary schools in which their own cultural identity is central. The representative of the Danish minority, Ms Gitte Hougaard-Werner, told the congress that a large majority of students who want to pursue higher education do so in Denmark. In turn, the Sorbian representative said that teachers are being recruited for their education system in Poland and the Czech Republic who can quickly master the Sorbian language after a short course and thus train the new generation of Sorbs.

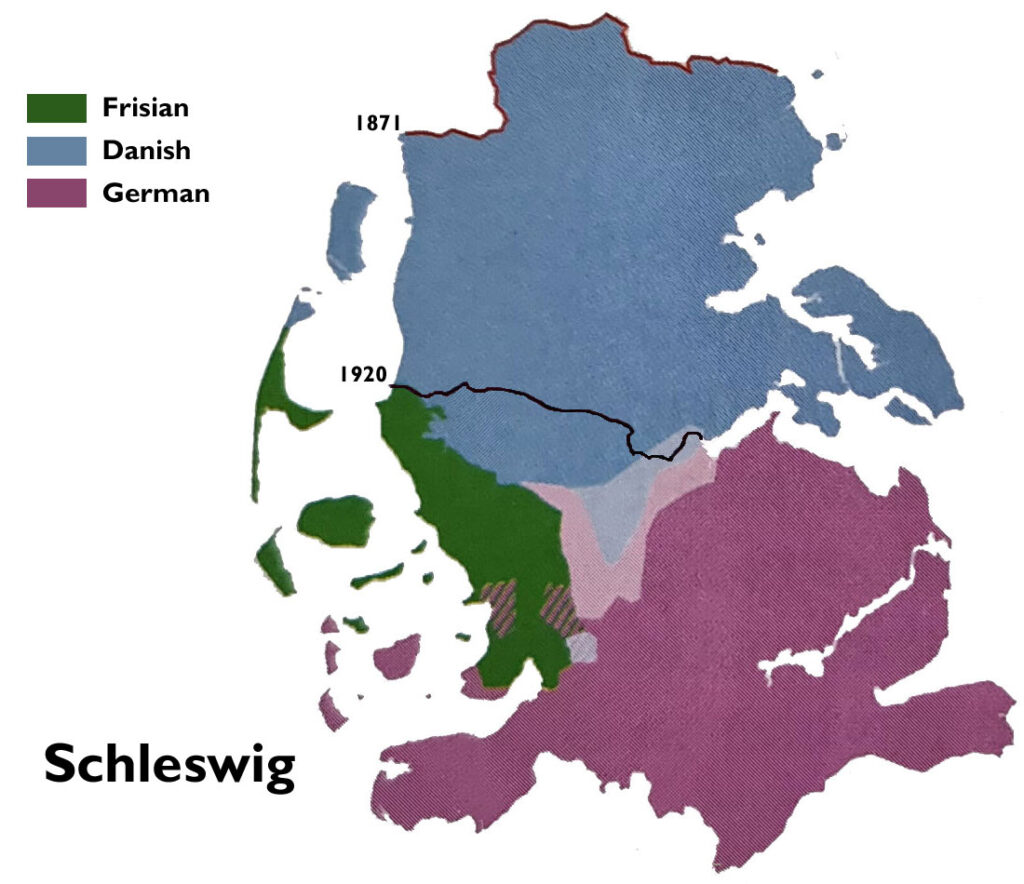

The imbalance in support for the various national minorities is not the result of the number of people belonging to the community; after all, the three communities have a comparable population size. The government support mainly reflects the geopolitical balance of power. This is particularly visible in Schleswig-Holstein. The Danish and (North) Frisian minorities are located in this northern German state. However, the latter are much less visible. The Danish minority has schools, while the Frisian minority has (voluntary) language lessons. Furthermore, on prestigious and political occasions, when national and international representatives meet in the state, support for the Danish minority is widely reported, while the existence of the Frisians is largely ignored.

The referendum without a Frisian choice

This situation is easy to understand from the perspective of the history of the area. After all, Schleswig was a border area where Denmark and Germany battled for regional supremacy for centuries. After World War I, following the Treaty of Versailles, a referendum was held that divided the area between Denmark and Germany. The results of the two referendums, in February and March 1920, determined the current borders between Germany and Denmark. The areas with a large majority of German or Danish speakers were added to the respective country. The new borders have also created the existence of small minorities on both sides of the border. The German minority in Denmark currently numbers around 15,000 people.

In the distant past, state borders ran along the lines of power, while in the twentieth century they ran on the basis of identity. Participation in the leading identity gives an individual access to all positions of power in society. The boundaries in the twenty-first century have become blurred and responsibilities, risks and the exercise of power have been dispersed. It seems that the Frisian-speaking community has mainly been given the risks.

The Frisians were ignored in this geopolitical game. Although the area was trilingual, the referendums in 1920 were solely about the future of the Danish and German communities and the control of the territory by Denmark or Germany. Although the Frisians formed a majority of the population in the North Sea area, they were forced to choose between two nationalistic options that did not do justice to the interests of the Frisian community.

Ultimately, in 1920, the Frisian community chose to stay with Germany. The fact that a large state usually shows more tolerance for diverse identities may have played a role in this choice. After all, a vast country almost always has more diversity within its borders and lacks the capacity to impose an identity on every single citizen. In the twenty-first century, state structures have become even larger. It may therefore be in the interest of the Frisian communities to focus now primarily on participation in the supranational structures of the European Union and the United Nations, rather than just that of a national state.

Now, more than a hundred years later, the friendships between Germany and Denmark are close and the German and Danish minorities in the border region are thriving like never before. The Frisian community, however, seems less vital. Frisian culture is limited to voluntary work, folklore and primary education. Frisian has in some respect not transcended its infancy, while the other national minorities have matured and participate at every level of society.

Discrimination

However, the representatives of the various Frisian organizations that attended the FUEN conference emphasized that there is fortunately no longer any discrimination. The times when the Frisian language was actively ridiculed and marginalized are over. There is now every freedom to use the language and pass it on to the new generation. Many other minorities are in a less fortunate situation and are still hindered by discrimination on a daily basis. Protection against discrimination is an important issue for minorities since it breaks the justice that underpins fair cooperation.

During the three-day FUEN conference, attention was paid to the discrimination experienced by the various minorities. For example, much attention was paid to discrimination against the German minority in Poland. Mr. Bernard Gaida, the chairman of FUEN’s German minorities working group, talked about the legislative changes introduced in Poland in February 2022. The new rules limit education in the German language. At the same time, subsidies are being reduced. However, these restrictions do not apply to all nine national minorities in Poland, but only to the German minority. He said the European institutions he approached stated that it is an internal, educational matter, while the German community considers it a human rights issue. Mr. Gaida called for combating this discrimination, which makes thousands of children second-class citizens.

This situation does not differ much from the one in which the Frisian community finds itself. Although the representatives of the Frisian organizations did not mention discrimination against the Frisian community, the Frisian language and culture are objectively allocated far fewer resources than comparable others. The freedom to protect and promote the Frisian language and culture is without the necessary resources only the freedom-of-nothing-to-lose, because you are unable to do anything. It is always the responsibility of the community itself to put discrimination on the agenda when there is an unfair distribution. If you leave this action to a more powerful group, you will be used as an instrument in a power struggle that will make you a slave of the victor who will sideline you when your usefulness is over.

The vitality of action-oriented communities

Compared to East and North Friesland, the position of the Frisian language in Fryslan is rock solid. Also in comparison with other minorities, such as the Catalans in Catalonia, the position of Frisian in society stands out positively. For example, there are percentage-wise more inhabitants of Fryslan who speak and understand Frisian than there are Catalans who speak and understand Catalan. The Catalan representative explained at the meeting that there is an active, society-wide movement to promote Catalan and the self-determination of Catalonia. For example, he wants to make the Catalan language mandatory for government officials in the region. After all, a minority language needs additional support against the pressures of the dominant language if it is to survive. He also passionately explained the political struggle for self-determination in Catalonia. This image contrasts somewhat with the limited social and institutional support for Frisian, which is characterized by shyness rather than a revolutionary spirit.

The representative of the Vlach community, Mr. Fudulea, talked about the way in which the Vlach manage their organization and development. The Vlach live scattered across the various Balkan countries and do not form a majority anywhere. They also receive no government support. They are therefore mainly aimed at stimulating small-scale entrepreneurship. This network offers people from the Vlach community in the smallest villages in the Balkans the opportunity to participate in economic life and thus form a vital community of self-conscious citizens.

A thriving future?

At first sight, the position of the Frisian language and culture seems stronger in Fryslan than in northern Germany, but this is not automatically a better starting point because a rapidly changing environment often requires revolutionary turns and mercilessly punishes passivity and shyness. The question is whether enough people find the Frisian language and culture valuable enough to promote it as a leading identity so that future generations continue to feel Frisian. It is not only the East and North Frisians who let themselves be sidelined when it comes to the protection and promotion of the Frisian language and culture. In Fryslan, too, more opportunities disappear than are created. For example, the second university in the Netherlands was located in Franeker, which was shut down in 1811 during the occupation by Napoleon, never to return. Since then, students have had to seek opportunities outside Fryslan if they wanted to study at the university. The Frisian identity has therefore not transcended its infancy in Fryslan either.

FUEN will hold another conference next year. The representatives of the Frisian organizations will undoubtedly participate again. Will the East and North Frisian languages move further away from West Frisian? Will the Frisian language then have a stronger, more mature position in society or will it move in the direction of a folkloric children’s language? Will there be a revival of Frisian identity that will move it past its infancy and put it on an equal footing with other national minorities? And what about the real West Frisians? After all, Fryslan is only the west from a German perspective. West Friesland consists of the northern part of North Holland, where the Frisian identity is hidden deep in the past. Will an organization of West Frisians also participate in the congress next year? The future will show which cultural identity people choose.