Introduction

The study of historical family ties using DNA testing has taken off in recent years, as it provides insights that were previously hidden. This article highlights a study of a family from the Frisian Northern Woodlands, a region in the Netherlands with a specific cultural background. The study examines the genetic relationship of the author and his grandmother and their relatives. The traditional view of genetic inheritance assumes that a person receives approximately 50% of his DNA from both parents. A generation ago, this means that grandparents contribute approximately 25% to a person’s DNA. Nevertheless, recombination, a process in which genetic information is pre-mixed and then passed on to future generations, introduces randomness into the inherited DNA. This study provides an example of genetic inheritance in which the effects of recombination have caused the grandson to be more closely related to his grandmother’s (distant) relatives than his grandmother herself.

The Frisian Northern Woods—A Historical Context

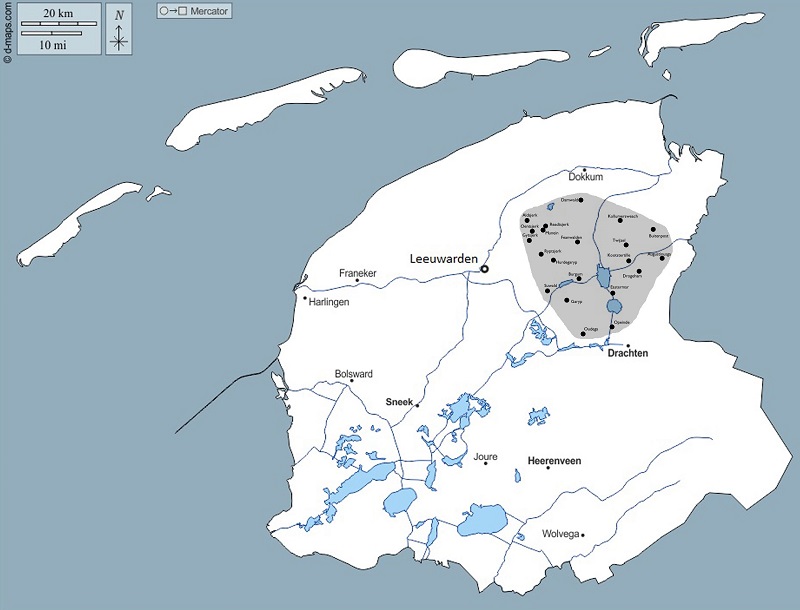

The Frisian Northern Woodlands (Noardlike Wâlden) is a historical, cultural region in Friesland, the Netherlands. The area is characterized by small, scattered villages, traditionally dependent on agriculture, peat extraction and later small-scale industries. Due to its geographical isolation and historical socio-economic circumstances, the Northern Woodlands have maintained a distinct cultural identity. This history provides a context for the genetic inheritance patterns observed in this study.

Methodology

To examine my genetic inheritance patterns in the Frisian Northern Woods and to understand why I have a closer genetic tie with my grandmother’s family compared to her, a structured methodology was adopted. That involved a careful collection of information through use of DNA testing platforms, comparative analysis of genetic matches, and analysis of recombination and inheritance trends in segments.

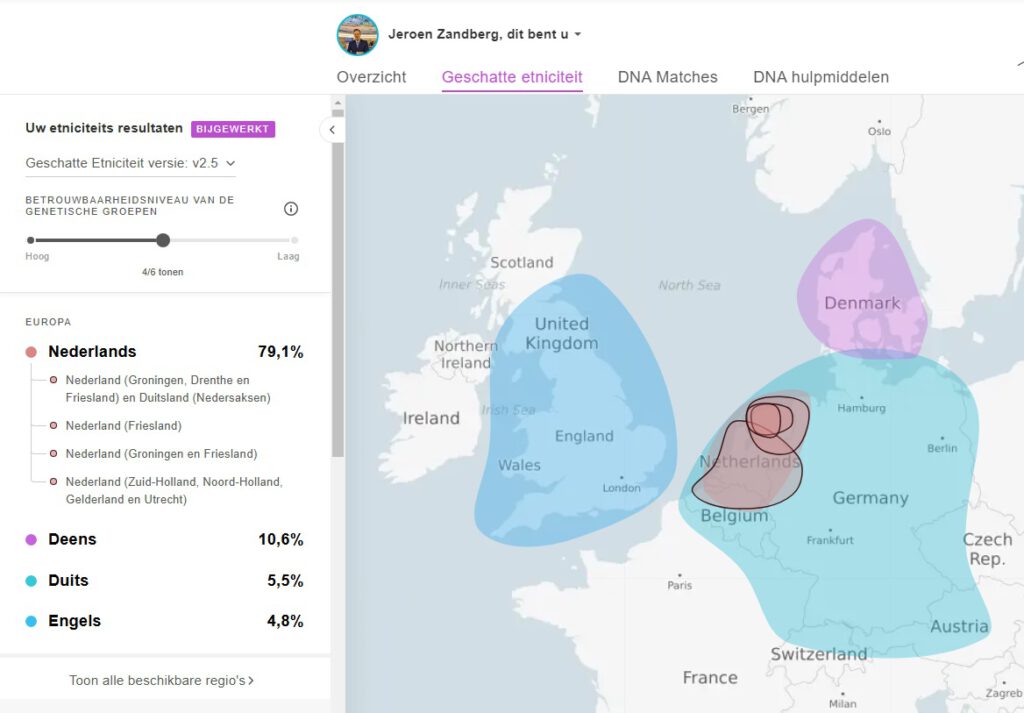

3.1 Data

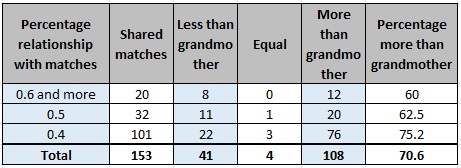

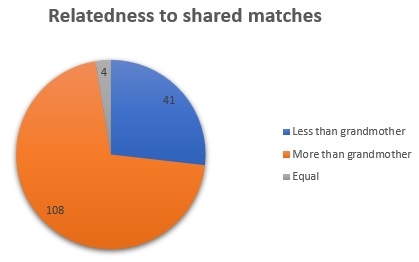

Information from my DNA test was acquired through the use of MyHeritage. Analysis of my grandmother’s and my genetic samples focused on shared matches, shared centimorgans (cM), shared segment sizes, and recombination and inheritance trends. The data set was extracted from a total of 651 genetic matches with 0.4 percent and more relatedness, 153 (24.6%) of whom shared a genetic match with my grandmother. Specific analysis focused on cases in which my genetic tie with our shared matches was stronger compared to my grandmother’s.

3.2 Comparative Analysis of Genetic Matches

For each shared match, I examined the proportion of shared DNA with my grandmother. As many as 70.6% (106 out of 153) of shared matches showed a stronger genetic tie with me compared to my grandmother. In addition, 83.7% of shared matches showed shared DNA with me that could not have been acquired through my grandmother but through a different grandparent. Historical genealogical documents, when accessible, were examined for shared ancestors in such matches.

3.3 Segment Inheritance and Recombination

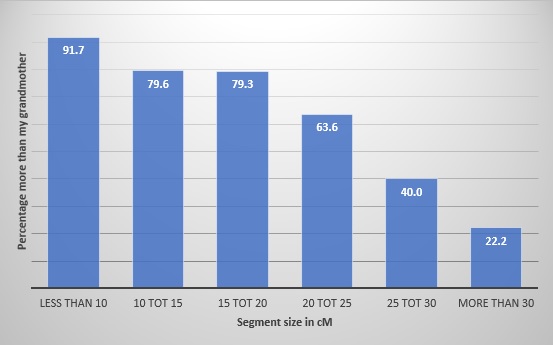

Segment sizes and chromosomal locations were analyzed to track inheritance patterns. Cases where I had a larger segment size than my grandmother with a specific match were identified and explored. The relationship between segment size and relative relatedness was categorized:

• Segments >30 centimorgans: More related in 22.2% of cases.

• Segments 25–30 centimorgans: More related in 40% of cases.

• Segments 20–25 centimorgans: More related in 63.6% of cases.

• Segments 15–20 centimorgans: More related in 79.3% of cases.

• Segments 10–15 centimorgans: More related in 79.6% of cases.

• Segments <10 centimorgans: More related in 91.7% of cases.

These results indicate that the smaller the segment size, the higher the probability that I am more related to the shared matches than my grandmother is, suggesting alternative inheritance pathways due to recombination.

3.4 Geographic Contextualization

Given the historical endogamy of the Frisian Northern Woods, the study also examined whether genetic similarities could be attributed to prolonged local intermarriage. The geographic origins of matches were mapped to identify patterns of regional inheritance. My grandmother was born and raised in Buitenpost, but part of her ancestry is from a specific region in Groningen. None of my other grandparents have any relatives in this region, whereas they do in the Northern Woods. It is likely that I inherited less DNA from my grandmother’s Groningen ancestors, contributing to the observed inheritance patterns.

The analysis shows that I am genetically more related to most of my grandmother’s relatives than she is to them. The observation seems to be determined by recombination and a historical practice of endogamy in the Frisian Northern Woods.

Results

4.1 Greater Genetic Affinity to Grandmother’s Relatives

Out of 153 genetic matches shared with my grandmother, 106 (70.6%) showed a stronger genetic tie with me compared to her. In addition, between 83.7% and 86.2% of the 153 matches included shared segments with me not received through my grandmother but through a different grandparent. This shows that recombination is responsible for a clustering of specific DNA segments in my genome that were inherited from my grandmother’s direct relatives and other grandparents.

4.2 Segment Size and Relative Affinity Relationship

Analysis of segment sizes revealed a specific pattern: the smaller a segment, the larger a chance my genetic tie with a match is nearer to me compared to my grandmother’s. This signifies that recombination doesn’t proportionately divide and assign segments of DNA between and through generations and that specific segments of the forefathers can survive and even amplify in specific descendant branches.

4.3 Groningen Connection and Impact of Endogamy

Most significant fluctuations in relatedness between my genealogical-connected and genealogical-non-connected groups of matches have been seen in Groningen-connected groups of my kin. In view of my grandmother’s family having relatives with a specific region in Groningen, but my other two sets of grandparents having no relations with that region, I must have received a reduced proportion of DNA through these Groningen forefathers and foremothers. That could partially explain why my genetic tie with many kin of my grandmother’s Northern Woods community is nearer to me in terms of kinship compared to her’s.

4.4 Implications for the Genetic Landscape of the Northern Woods

The findings confirm that Northern Woods’ DNA heritage patterns have been impacted by long-standing localized social conventions and endogamous behavior, with important consequences emerging in relatively insular environments. Most of the shared genealogical relationships cannot be traced to a specific recent common ancestor, partly due to gaps in genealogical records. Nevertheless, the durability of such genetic correlations reflects a shared heritage that must have developed over the past 200 to 300 years. Overall, this study presents a nuanced understanding of genealogical restrictions and heredity, challenging a reductive view of a single, unilinear path of DNA transmission.

Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Endogamy and Genetic Relationships

Historically, the Frisian Northern Woods was most likely a comparatively isolated area, with minimal migration and a preference for intra-community marriage. This practice has probably maintained high genetic stability in the long term, with many individuals possessing DNA from common ancestral lines. This can explain why, in many cases, I am more genetically similar to my grandmother’s family members than she is herself, since certain DNA segments have been copied multiple times through successive inheritance from common ancestors.

The difficulty of finding recent common ancestors for the majority of the shared matches is a reflection that a substantial portion of the shared DNA in the data set originates from earlier times, most likely far beyond the range of well-documented genealogical records. In addition, highly inherited segments among numerous distant relatives point to a persistence of genetic continuity in the area.

5.2 Case Study: Rein Sierks Roosma

One example is a genetic match with a person who is a direct descendant of Rein Sierks Roosma, born in 1736 and died in 1800 in the town of Burgum. My grandmother is also a direct descendant of the same ancestor on her father’s side. But while I have 1.0% DNA in common with this individual, my grandmother has only 0.8%. This indicates that I inherited more genetic data from this ancestor as a result of recombination, supporting the findings that inheritance is not always linear and divided equally between generations.

5.3 Genetic Relatedness

The MyHeritage report indicates that my grandmother and I share 1,982.3 centimorgans (cM) of DNA, which constitutes 28.0% of the entire genome. We also share a largest segment of 267.2 cM, hence indicating a close genetic relationship. The percentage, nevertheless, should not be assumed to be direct inheritance from the grandmother exclusively. Rather, it is made up of DNA fragments inherited from my grandmother, with overlapping fragments from my grandfather and possibly other grandparents because of shared ancestry. The results suggest the operation of other than direct lineal inheritance mechanisms. In light of the fact that I am generally more related to the shared matches than my grandmother, might indicate that I inherited slightly less than 25% from her. It is possible that I got around 23–25% of my genetic material from my grandmother and the remaining 3–5% may be from my grandfather or may represent a remote common ancestry between them or other grandparents. These findings validate the hypothesis that historical endogamy in the Frisian Northern Woods has created a genetic landscape in which individuals are more related than the genealogical record may indicate, highlighting the subtlety of genetic inheritance in historically insular populations.

5.4 Implications for Genealogical and Genetic Research

The findings of this study challenge traditional assumptions about linear genetic inheritance and highlight the need for more complex analyses of DNA test results. In regions that have been historically insular, like the Northern Woods, genetic affiliations can be determined more by ancient ancestral descent than by modern genealogical affiliation.

For genealogists, this study emphasizes the importance of considering recombination effects and local endogamy in interpreting DNA matches. Multiple distant relatives may share more DNA than would be anticipated by virtue of long-term genetic continuity rather than recent common ancestors.

The full report titled “More Related Than the Source: A Genetic Analysis of Ancestral Relationships in Friesland’s Northern Woods and Groningen” can be downloaded from Academia.edu